Marta Kupis

Uniwersytet Jagiellonski, Poland

The 27th edition of Pol’and’Rock Festival (formerly known as Station Woodstock) in 2021 took place in very unique circumstances. The COVID-19 pandemic may not be over yet, but in Poland many restrictions have been loosened in light of the vaccination program, and cultural events are coming back to life. In the case of Pol’and’Rock – “the most beautiful festival in the world” – this meant a break from last year’s very harsh restrictions, but continuation of those still in place. Most importantly, this included a limited audience (up to 20,000 people, including 250 without valid vaccination certificates) which meant that for the first time in the festival’s nearly thirty year history it was necessary to buy tickets. Unfortunately, I did not gain entry. Fortunately, this allowed me a glimpse into the less formal side of how the festival’s fans were coping with a situation of ‘twofold liminality’ they found themselves in.

The underlying theoretical perspective framing this description of Pol’and’Rock’s 27th edition is that of liminality as developed by Victor Turner. This applies both to the general situation of the event – standing in between last year’s very strict limitations and a slow “return to normality” – and the unique case of those people who could only gain partial access to the concerts. At the same time, music festivals themselves were frequently analyzed through the lens of liminality and ritual, including by Turner (1982) himself. Classically, liminality has been understood as a state “in between”. The liminal phase of a ritual is characterized as a time when a person, usually a participant of a ritual of passage, is already beyond a pre-liminal stage, such as childhood, but not yet accepted as a member of a post-liminal stage, for example adulthood.

In the context depicted here, pre-liminality is understood as, on the one hand, the state of the COVID-19 pandemic and the accompanying restrictions (as a side note, it is worth noting that they themselves can be viewed as a liminal stage), while the post-liminal phase is the hopeful time following its end. Of course, this framing is somewhat questionable. For example, there is no specific moment in time or a threshold in the number of vaccinated people that would mark the definite end of the coronavirus epidemic, and an increasing number of medical specialists are pointing out that many of the behaviours developed in this time are likely to be here to stay. Nevertheless, for a layperson’s imagination “return to normality” would be marked by being once again allowed to participate in social gatherings and cultural events, and as such here it is understood in this way. In this context, liminality is viewed as the unique circumstances when some events are allowed to take place, but many restrictions are still in place. On the other hand, this text also focuses on the group of people who would like to partake in the festive ritual but could not join the actual festival with its spatially restricted campsite and good access to live music. With this framework in mind, it seems appropriate to move onto the description of the festival itself, as well as the unique group analyzed here.

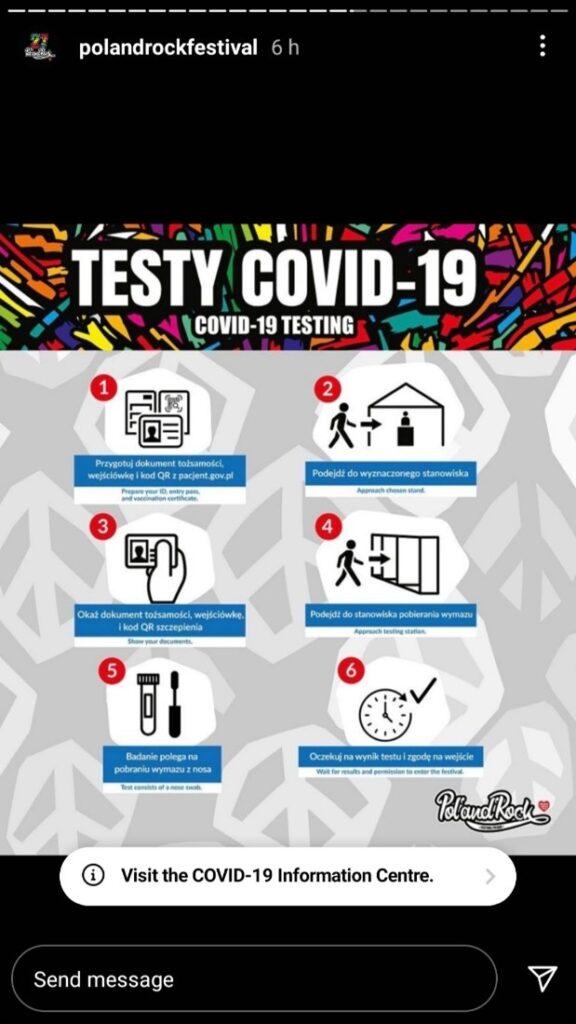

The 27th Pol’and’Rock Festival took place between 29th and 31st July 2021 in a new location, Płoty in West Pomerania. Through strict formal entry procedures, the event was very well protected from anyone with coronavirus. Most importantly, for the first time in the famously free festival’s history tickets were introduced, and identified with the name and surname of the person entering to prevent them being resold outside the official capacity. The entry fees were low at 50 zlotys (around 12 Euros) and were distributed in a number corresponding to those currently allowed at social gatherings in Poland, that is 20,000 participants, including 250 unvaccinated people. Additionally, everyone including those with a vaccination certificate was tested for the virus before entering for free, but anyone leaving and re-entering the campsite was required to take the test again, but this time with a payment. It should be noted that the festival infrastructure was well organized, especially considering that it was the first time it took place in a new location. Special trains were travelling between Szczecin and Kołobrzeg, and the festival-goers were picked up from the train station by buses, which would take them to a spot a short distance away from the actual festival space. The line-up of Pol’and’Rock included performers both from Poland – such as Dżem, Raz Dwa Trzy, Renata Przemyk, Pidżama Porno or Kroke – and from all across the world, including Morgane Ji and Slift, with the latter giving their first concert in Poland (Zespoły, z którymi planujemy spotkanie na Festiwalu, n.d.).

Unfortunately, I could not obtain a ticket. While the organizers were insisting that watching and interacting with the event online – on YouTube, Discord or Twitch – is “just as valid” a form of participation in the festival, and indeed those on stage would make callouts to what was written online. It appears that for many this type of participation proved insufficient, or felt somehow incomplete. The advantages of this sorry circumstance proved to be quite rewarding for me, though. First, I probably would have never taken interest in the contests organized by the festival’s partners, which turned out to be an interesting way of activating the potential audience’s creativity. Those who would like to try their chance at winning the tickets were asked to, for example, create unique wishes for an unknown participant or say what they cannot imagine their summer without. Secondly, and more importantly, I had a glimpse into the grey area which emerged around Pol’and’Rock. Many people would come without a ticket, hoping to get one by the entrance or to be allowed into the campsite without one, but were firmly, though politely, turned away by the volunteers. In fact, they would even suggest to me that I join some of the people already present in their “alternative party”. Indeed, those standing by the queue would dance, play their own music or just stand by the fence, screaming their disappointment in the direction of the main stage. Additionally, the citizens of Płoty quickly noticed that the unfortunate non-attendants might prove a goldmine, offering a private campsite right by the fence of the festival. In various online discussions there emerged a suggestion that an alternative Pol’and’Rock be organized in Kostrzyn, the place where it took place over the last few years, though if this initiative succeeded, it left few lasting marks in the community. Last but not least, it should be mentioned that Station Jesus – a festival organized as a Christian or even evangelistic event alternative – also took place this year. Some of the participants would migrate between Station Jesus and the former Station Woodstock, interacting with those hopelessly standing by the latter’s entrance. Their input was rarely as welcome as it was this year.

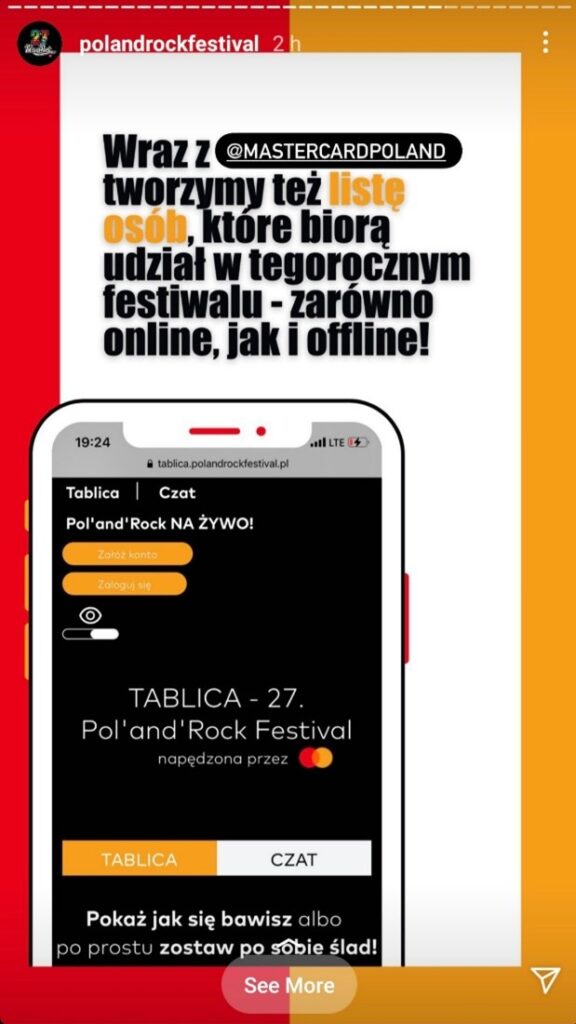

The people described above are characterized by a strong sense of subjective identification with Pol’and’Rock community. Many of the interviewees stated that they partook in earlier editions, which is what prompted them to travel to the festival site, even without assurance of entering the main festival, though it should be noted that most of them declared that they live in relative proximity to Płoty (for example, in the same voivodship). Similarly, and this time encouraged by the organizers, a sense of community could be found among online participants of the 2021 edition of Pol’and’Rock Festival. In this case, the unique phenomenon of the pandemic could be observed, namely that of the unity of time replacing the unity of space, which usually creates the liminal character of a music event. Of course, this liminality is limited given the circumstances of the event, with participants devoting their time to listening to the festival while also taking part in their everyday activities. This is largely the source of the title of this blog entry. For the organizers, it was crucial to ‘manage’ the liminality of Pol’and’Rock as much as it was possible. Firstly, the Turnerian anti-structure typical of music festivals was much smaller than usual due to the ever-present pandemic restrictions. Secondly, and partially contradicting the former statement, there were visible attempts at making the restrictions of this liminal stage between pandemic and post-pandemic times as unobtrusive as possible. Lastly, despite encouraging partying by the campsite’s entry, it was necessary to limit such non-participation, so that a general sense of the event’s uniqueness was maintained. On the whole, however, the 27th edition of Pol’and’Rock proved to be a truly exceptional experience, not in the least because of people’s willingness to join the event – to partake in this liminality – limited as it might be.

References

Turner, V. (1982) Celebration. Studies in Festivity and Ritual. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press.

Zespoły, z którymi planujemy spotkanie na Festiwalu. (n.d.). Accessed August 30, 2021, from https://polandrockfestival.pl/kto-zagra